In late February, the federal government released a final rule that makes regulatory changes to the Child Care and Development Fund. The rule requires action from many states to ensure child care is affordable and accessible for families that qualify for child care subsidies. This new rule encompasses policies that touch on several aspects of the child care subsidy system, including provider reimbursements and affordability of care. The federal government estimates that 800,000 families and 1.3 million children will be impacted by the new rule, and that these new requirements will ultimately transfer approximately $206.6 million in child care costs from families and providers to states.

Our analysis shows how states’ implementation of these new requirements may result in valuable savings for families, while also supporting child care providers. With adequate funding, these state policy shifts could lead to a more comprehensive approach to child care subsidies, ultimately benefitting families across the country.

Overview of the New Rule

Under the new rule, states are required to make several policy changes to their child care subsidy systems, which, taken together, are intended to lower child care costs for families, improve provider payment rates and practices, and simplify enrollment. Our analysis illustrates the impact of some of these provisions on families and providers, including:

- capping copayments at 7% of family income,

- reimbursing providers based on enrollment rather than attendance,

- paying providers prospectively—or in advance of services—and,

- developing grant and contract models for subsidized slots.

States are encouraged, but not required, to make child care more affordable by waiving copayments for families with incomes at or below 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL). States are also encouraged to adopt a policy that may incentivize more providers to enter the subsidy system—paying providers the full subsidy amount even when it exceeds the private pay rate.

The rule becomes effective on April 30, 2024, but noting the short timeframe between the rule publication and effective date, states have the option to request a 2-year, non-renewable waiver.

Lowering Family Copayments Results in Measurable Savings

In our 2023 Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap, we calculated the maximum copayment possible for a family receiving child care subsidies in each state and found that at least 26 states and the District of Columbia will need to make policy adjustments to ensure all families pay copayments of no more than 7% of their income.

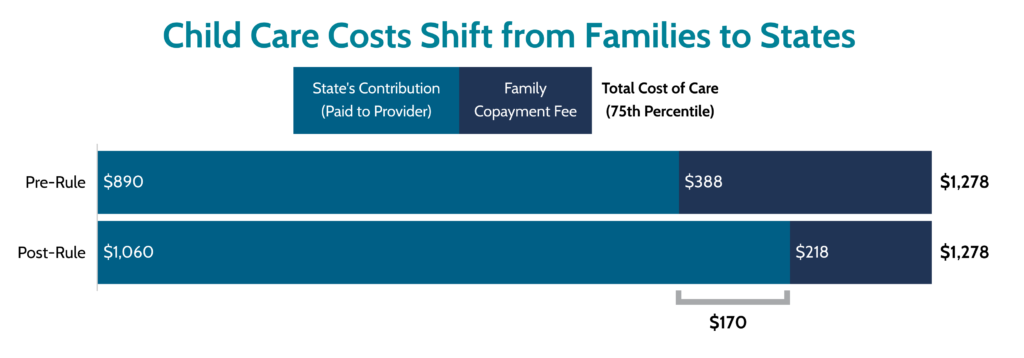

The impact of the new copayment cap on cost savings for a simulated family of three with an income at 150% of the FPL is depicted in the graph below. Generally, once the copayment cap is implemented, costs will shift from families to states—with cost savings for the simulated family ranging from $33 per month to $170 per month, depending on the state.

Notes: Data for this measure are based on monthly child care subsidy rates and copayment fees for a family of 3 with an income at 150% of the FPL ($37,290 annually in 2023), with one infant in center-based child care. In this simulation, the provider is reimbursed at the 75th percentile of the total cost of care.

Prior to the new rule, the simulated family was paying 12.5% of their income per month in child care copayments. The shift to a 7% copayment cap decreases this family’s copayment by $170 per month—saving them $2,040 per year. Pre-rule, the provider reimbursement rate was composed of a 70% state contribution and a 30% family contribution. Post-rule, the state pays 83% of the provider reimbursement rate and the family pays the remaining 17%.

Hand in hand with the required copayment cap, states are encouraged to waive copayments for families at or below 150% of the FPL—which would encompass our simulated family above. If this state were to adopt the copayment waiver policy encouraged by the federal government, this family would have no out-of-pocket child care expenses, and the state would pay the full reimbursement rate amount, $1,278 per month, to the provider. Currently, families at 150% of the FPL are required to pay copayments in 45 states. Depending on state, broad adoption of this policy change could save families up to $388 per month.

Improving the Stability of Payments to Providers

In addition to lowering costs for families, there are a few key changes within the new rule that are intended to improve payment stability for existing providers and to incentivize more providers to participate in the subsidy system:

- Prospective payments: Paying providers prospectively—in advance or at the start of services—ameliorates long-time concerns with payment delays, which can impact providers’ economic solvency.

- Enrollment-based reimbursement: Paying providers based on enrollment helps to stabilize their income, by ensuring that they are paid based on the number of children who reserve a spot in their program, regardless of whether the child ultimately attends. Previously, most states paid providers based on attendance, which leaves them with the unpredictable responsibility of covering the cost of any reserved slot that is not regularly filled.

- Grants and contracts: States will be required to enter into contractual agreements with providers to designate some slots for subsidy-eligible children in underserved geographic areas, infants and toddlers, and children with disabilities. In addition to traditional subsidy certificates or vouchers, this requirement is intended to lead to more stable revenue for providers and child care availability for specific groups of children.

- Subsidy rate exceeding private pay rate: States are encouraged to allow providers to be paid the full amount of subsidy reimbursement, even if that amount is greater than the rate paid by families who do not receive subsidies (private pay rate). This change is intended to incentivize more providers to accept subsidies, because in some instances, the reimbursement rate for a subsidized slot may amount to more than what families without subsidies are charged. Though states have been allowed this flexibility in the past, the federal government hopes to standardize this practice by codifying it.

Whole System Approach

This new rule is intended to improve child care affordability for families while ensuring that new and existing providers can more feasibly sustain their businesses. Though this rule could set the groundwork for a more systemic approach to child care subsidy policy—subsidy programs need adequate funding to meet both of these overarching goals. Without adequate funding, existing challenges and imbalances within the subsidy system could be exacerbated. For example, increased resources dedicated to improving affordability in some states could leave fewer resources for expanding eligibility, increasing reimbursement rates for existing providers, and evaluating the true cost of providing quality child care.

The provisions outlined in the rule may, ultimately, spur further state and/or federal investment in the system such that the system can be improved holistically. As we detail above, copayment caps and copayment waivers will undoubtedly improve the affordability of child care. Taken alongside improved revenue stability for providers, and incentives for provider participation in the subsidy system, the policy shifts that emerge from this new rule have the potential to impact both access to, and affordability of, child care for families across the country.