Demand for subsidized child care slots is already very high. State subsidy programs simply do not meet the need. In many states, families are left lingering on waiting lists—unable to work or forced to use expensive or low-quality care options. So why would states want to increase demand even further?

The answer lies in the broader impact of subsidy programs. Child care subsidies do not just help an individual family. Well-funded, well-structured subsidy systems have the potential to increase supply and quality of child care for everyone, while improving educator wellbeing and stabilizing the industry as a whole. To reach this potential, however, the system must have a broader reach.

In the second blog post of this four-part series, we discussed state policy choices that can improve the supply of child care subsidy slots. In this post, we describe policy levers that can balance local supply and demand for subsidies and remove barriers to an otherwise equitable, functioning market.

Adequate Funding and Expanded Eligibility Increases Subsidy Demand

Participation in child care subsidy programs is not low because of lack of interest, but because of low funding and narrow eligibility. Some states have chosen to restrict the demand for subsidies by limiting the number of people who are eligible. One method used by states is to set the income threshold to near poverty. Another method is to exclude families who choose not to seek child support from noncustodial parents.

Unfortunately, low participation in child care subsidy programs limits the impact of policy levers that increase child care supply. These levers become relevant to only a small number of child care slots. Reimbursing slots at the true cost of quality care, for example, cannot meaningfully stabilize program revenue if child care programs only have one or two subsidy users enrolled.

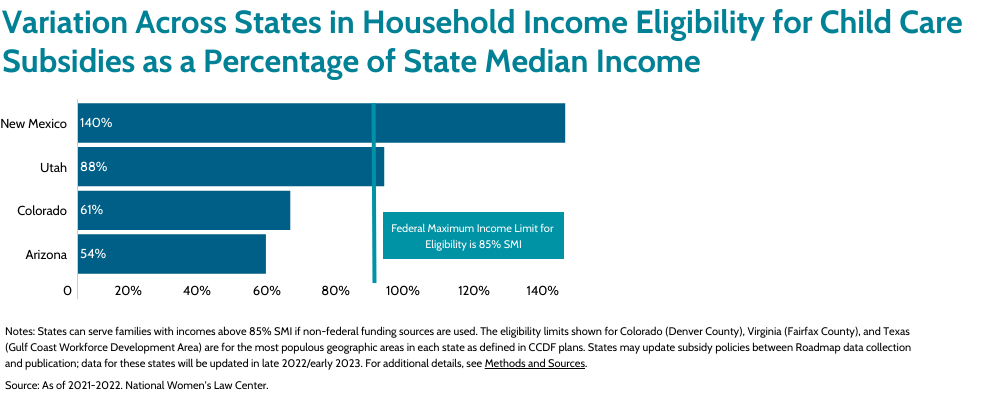

To increase demand for subsidy slots, states can choose to expand both funding and eligibility. Federal funding helps cover the costs of subsidies for families making up to 85 percent of the state median income. But states can also invest their own funds—as several states have done, including New Mexico, Louisiana, and California—to expand eligibility even further and to bring already-eligible families off of waitlists. These states have identified sustainable funding sources, rather than relying on allocation of general revenue funds.

As an example of the variation in state policies, below we show income eligibility thresholds as a percentage of the state median income for the Four Corners region of the US.

When paired with sufficient funding, state policies that increase demand for subsidies can work in partnership with policies that increase supply to expand child care access for families and stabilize the market.

Funding, however, must come first. Without additional supply, additional demand only makes waiting lists even longer.

Administrative Burdens, Out-of-Pocket Costs, and Other Roadblocks to Using Subsidies

In theory, when a subsidy-eligible family finds an open subsidy slot at a high-quality local center, the family could take the slot. In reality, barriers may reduce take up of subsidized care.

Administrative burdens act as one such barrier. In all states, families must apply for subsidies, but states vary in terms of how burdensome that process is—how confusing or time-consuming the application is, how often families need to reapply, and how long the application processing takes. As a result, administrative burdens play a role in how likely families are to use subsidies.

Child care programs contend with administrative burdens, too, in the form of complex paperwork, reimbursement delays, and frequent reporting requirements. Administrative burdens can strongly disincentivize subsidy participation on both sides of the market.

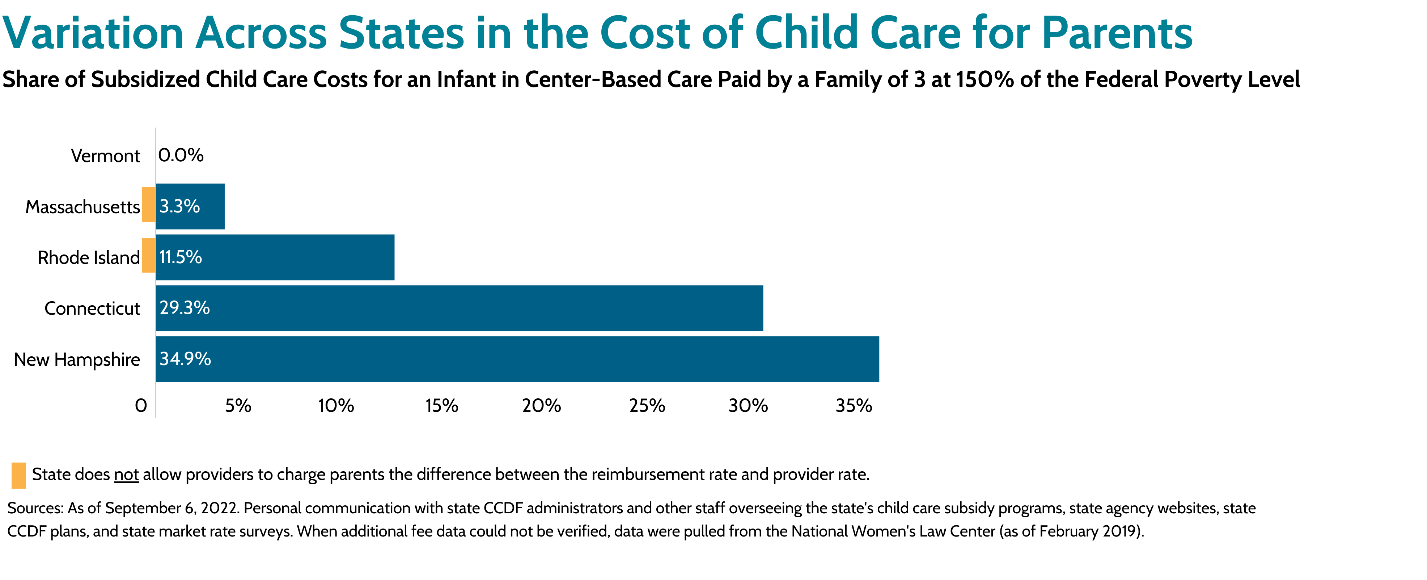

Out-of-pocket costs can also discourage participation. Many states require copayments (i.e., cost-sharing), and some programs charge additional fees to make up for the difference between subsidy reimbursement rates and what they charge unsubsidized families. In some states, copayments and fees can even make subsidized care less affordable than care from nonsubsidized programs.

State policy can keep costs lower for families by preventing programs from charging additional fees to subsidized families, as in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In the absence of this policy, and with reimbursement rates that are too low to cover the cost of care, families with low incomes pay much more. Critically, elimination of these additional fees is good for families, but—in the absence of adequate reimbursement rates—can further stress the margins for child care programs.

Finally, parental care preferences and the geographic distribution of child care can reduce subsidy demand. When it comes to child care, families have different preferences and priorities. Some parents may prefer a specific care setting or a provider with cultural, linguistic, or religious congruence to their own family. Without enough local facilities to meet these criteria that also accept subsidies, families may opt out of the subsidy system entirely.

State Policy to Balance Local Supply And Demand

The income threshold for subsidy eligibility is one of the most powerful levers that state leaders can use to shift more families into the subsidy system. When states combine a higher income eligibility threshold with lower out-of-pocket costs and reduced administrative burdens, demand for subsidized child care increases. If the state pairs these policy changes with sufficient funding, the number of families using subsidies should increase as well.

Increased subsidy participation fosters healthy market competition by incentivizing child care programs to strive to attract eligible families—especially if levers that increase demand and reduce burdens are paired with higher reimbursement rates.

The market rate for child care is artificially low because many families cannot afford to pay the true cost of providing quality care. But what if families who cannot afford to pay the cost themselves start using subsidies that reimburse at the true cost? Child care program revenue could stabilize, and programs could improve the quality of their services, expand their capacity, or offer additional services to families. Low-income families would not only have more choices, but over time, child care capacity and quality would have the potential to improve for everyone.

Finally, targeted workforce development programs—such as scholarships and stipends for bilingual educators, professional development opportunities to build the skills of local providers, and additional wage supplementation in underserved areas—can encourage more providers and educators to work in early childhood education, ensuring that those caring for children are from similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds as the children for whom they care.

States’ Power to Stabilize Markets

Many state policies influence the supply of and demand for child care subsidy slots. States determine how subsidies are distributed and funded, who is excluded from benefitting, how many hurdles are placed in the way of family and program participation, and whether reimbursement rates are high enough to incentivize quality.

These policies work together in a dynamic system. The many levers shape how well the subsidy system works, for whom, and the extent to which subsidies impact the rest of the market. By understanding supply and demand in the child care subsidy market—and investing in policy levers that impact both—states can address the underlying economic factors contributing to the current market failure.

In our final post of this series, we will shine a spotlight on two states. We will show how each is working to address the child care crisis using levers that impact supply and demand in the subsidy system.

Don’t miss the final post! Sign up to receive our emails, and be sure to check the option to receive announcements about new blog posts.