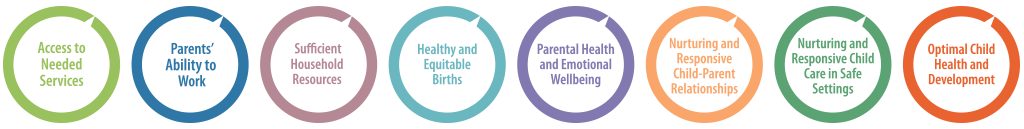

Child allowance is theoretically aligned with these policy goals:

SUMMARY

Child allowance is theoretically aligned with these policy goals:

International and United States-based research on cash transfer programs and child tax credits suggests that a permanent child allowance policy implemented in the US could significantly reduce child poverty, narrow racial disparities in household resources, and have positive impacts on birth outcomes, on child health from infancy through adolescence, and on child-parent relationships. However, further causal research is needed to establish the impacts of permanent child allowances in the United States on the prenatal-to-3 period.

The United States is an outlier among peer countries in that it does not have a permanent, universal child benefit policy in place to support families with children. Many countries offer a permanent child allowance or child benefit—a recurring, universal, unconditional payment to supplement the incomes of families with children, typically disbursed monthly until children reach age 18. The US offers a child tax deduction and child tax credit to defray the costs of raising children, and federal legislation recently increased the generosity of the child tax credit for 1 year and began the option of monthly payments. This temporary expansion may become permanent with further legislative action. Monthly payments to families in the US began in July 2021, and survey data suggest that the payments have reduced family food insecurity and child poverty.

International evidence and results from unique cash transfer programs in Alaska and North Carolina indicate that a permanent child allowance could significantly reduce child poverty in the US, without producing negative impacts on labor force participation or earned income. Cash transfer programs in the US have been shown to yield positive ripple effects on outcomes such as birthweight, child health, and child-parent interactions. Rigorous simulations and analyses have estimated that a child allowance policy in the US could potentially reduce child poverty by more than 50 percent. In addition, scholars estimate that the benefits to society would amount to over eight times the investment in a US child allowance. Evidence on child allowances and universal cash transfer programs continues to build quickly as new pilot programs are being implemented around the country and as US households receive the new expanded child tax credit.

Download the Complete Evidence Review

Child Allowance Evidence Review (PDF)

Recommended Citation:

Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. (2021). Prenatal-to-3 policy clearinghouse evidence review: Child allowance (ER 22B.1021). Peabody College of Education and Human Development, Vanderbilt University. https://pn3policy.org/policy-clearinghouse/child-allowance

Updated October 2021