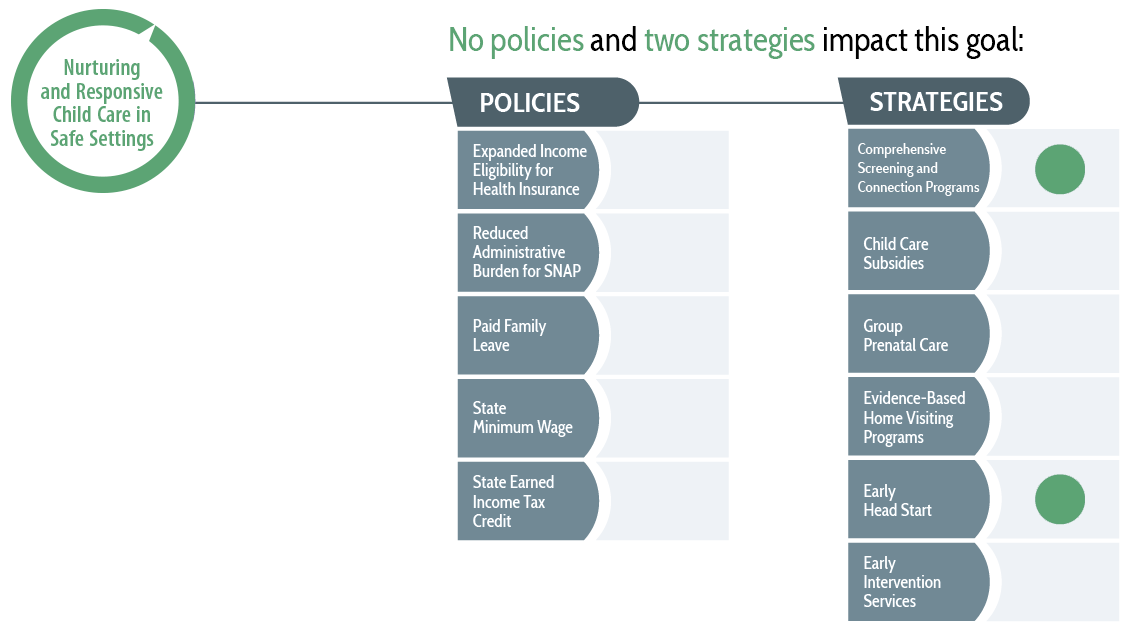

Effective policies and strategies to impact this goal include:

When children are not with their parents, they are in high-quality, nurturing, and safe environments.

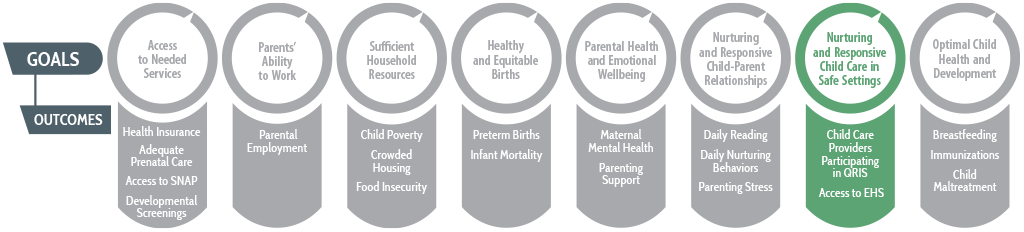

WHY IS NURTURING AND RESPONSIVE CHILD CARE IN SAFE SETTINGS AN IMPORTANT PRENATAL-TO-3 GOAL?

The developing brain of a young child depends on secure attachments with caregivers. Serve-and-return interactions—in which adults respond consistently and appropriately to a child’s cries, babbles, and other bids for connection—provide vitally important positive stimulation and protect the developmental process from disruption due to stress.1 These interactions, so fundamental to shaping brain architecture, are just as important when children are in child care as when they are at home with their parents. But just as parents need support so that they can focus on connecting with children, so do caregivers in child care settings. Education and training, financial security, food security, health and wellbeing—all of these factors can affect caregivers’ interactions with children.2,3,4 But research shows that child care workers commonly earn wages insufficient for meeting basic needs and that they experience high rates of food insecurity, as well as poor mental wellbeing.5 Those caregivers who work with infants and toddlers typically earn even lower wages than their peers who work with children ages 3 to 5.6

As of 2019, more than 12 million children under five were in some form of child care in the United States.7 The science makes clear that financial hardship, poor health, and threats to emotional wellbeing diminish the quality of caregivers’ interactions with young children. However, it remains unclear how best to leverage components of child care—such as subsidy rates, workforce qualifications and compensation guidelines, or class sizes and child-caregiver ratios—to improve these interactions. Observational tools, such as the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) and Environment Rating Scales (ERS), can be used to track and assess classroom safety and quality, but “process” quality in particular (the richness of classroom interactions and learning experiences) can be difficult to identify and measure, and implementing the tools can be costly.8 These tools are evolving and improving to accommodate the growing awareness of young children’s unique developmental needs,9 but in the meantime working parents still must make decisions about how best to ensure quality care for their children.

Data show that only 24% of infants and toddlers are placed in child care considered to be high quality by established standards.10 Affordability and proximity of care each play a critical role in determining families’ child care options. Child care typically accounts for a substantial portion of a family’s budget, approximating—and often eclipsing—the cost of housing.7 Families who live in low-income neighborhoods typically have fewer child care options than families in other neighborhoods, a factor that limits access to affordable, quality child care— especially for those children for whom quality care is particularly important—and perpetuates existing racial and socioeconomic disparities.11,12,13

MEASURING STATE PROGRESS TOWARD ACHIEVING THIS PN-3 GOAL IS DIFFICULT

It is critical that young children receive quality care and that their caregivers have the resources they need to provide that care—and yet currently no outcome measured nationally provides sufficient insight into states’ most effective means of achieving this goal. There is a lack of rigorous research that establishes causal links between states’ policy efforts and child care quality and children’s outcomes. Rigorous research that focuses specifically on infants and toddlers is even more sparse. Another challenge is that states and researchers rely on definitions of “quality,” using tools such as CLASS and ERS, that have been slow to accommodate child-caregiver interactions as a central component, and seldom link directly to improvements in children’s outcomes. It is imperative that these tools continue to improve and that the evidence base grows to fill in these gaps.

According to our comprehensive review of rigorous research, Early Head Start (EHS) can be an effective strategy for improving outcomes for young children and families. EHS, a program serving low-income pregnant women, infants, toddlers, and their families, provides children with individualized services and high-quality early care and learning environments, and builds parents’ skills and community connections. A quality improvement and rating system (QRIS) can encourage the adoption of models of care like Early Head Start (EHS). A QRIS can help to eliminate barriers to quality care and disparities in access, by systematically assessing and providing public information about child care quality. These systems have the potential to be a valuable source of information for families and a means of offering providers incentives for, and assistance with, improvement. States can tie this mechanism to licensing procedures and use it both to set requirements and to promote recommended practices among participating providers. Many of the elements that contribute the success of EHS—such as standards for parent engagement, child care coaching, workforce compensation and qualifications, and class sizes and ratios—can be found in QRIS standards as well.

Given that EHS provides high quality and nurturing care to infants and toddlers, states should track the percentage of income-eligible children who participate in EHS. Additionally, given the potential of QRIS to inform families about the quality of child care available and to encourage providers to improve their quality, states should monitor the proportion of providers that participate in their QRIS. The following sections provide an overview of these and other strategies states may use to support nurturing and response child care.

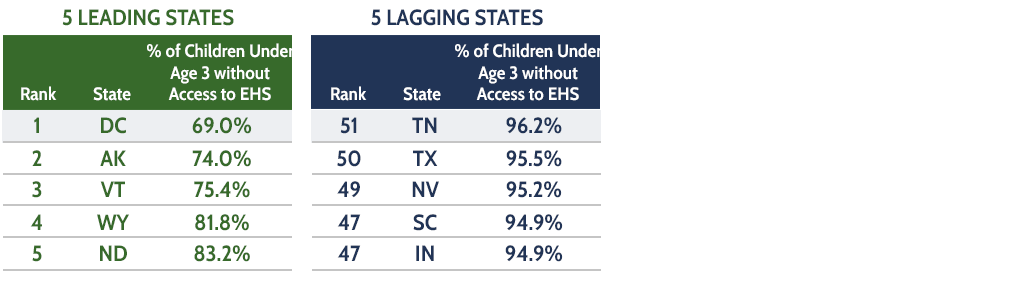

Outcome measures were calculated intentionally in the negative direction to demonstrate where states have room for improvement and to help states prioritize the PN-3 policy goals. Out of 51 states, the state lagging furthest behind ranks 51st, and the leading state ranks first. The median state indicates that half of states have outcomes that measure better than that state, whereas half of states have outcomes that are worse. Importantly, the “leading” state on a given outcome does not necessarily indicate a target for all other states to strive toward; even in the states with the best outcomes, many children and families are struggling.

OUTCOME MEASURE: LACK OF ACCESS TO EHS

% children without access to Early Head Start

Median state value: 90.9%

Due to limited federal funding and supplemental state investments, few income-eligible children are able to participate in EHS. Currently, the percentage of eligible children who do not receive EHS services nationally is 92.0% and ranges from 96.2% in the state lagging furthest behind (Tennessee) to 69.0% in the leading state (the District of Columbia), with the median state failing to serve 90.9% of infants and toddlers. The percentages refer to children without access to funded slots for Early Head Start. More children may actually be served by Early Head Start, but state funding influences the slots available.

Source: 2019 Early Head Start (EHS) Program Information Reports (PIR) and 2018-2019 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS).

OUTCOME MEASURE: LACK OF PARTICIPATION IN QRIS

% providers not participating in the state’s quality rating and improvement system (QRIS)

Median state value: 45.3%

Although state QRIS structure, standards, and incentives vary considerably, and the current evidence base does not make clear which elements of a QRIS lead to better child outcomes, provider participation is key. If providers do not participate in the state QRIS (or the state does not have a QRIS), the state lacks a mechanism for holding providers accountable and parents cannot evaluate the quality of providers. For these reasons, QRIS participation is an important indicator of providers’ compliance with state guidelines. Participation in QRIS may be voluntary, compulsory (e.g., tied to a state’s licensing requirements), or some combination thereof. Participation varies substantially across states. According to the most recent data available from the Build Initiative & Child Trends’ Quality Compendium data system, six leading states (CO, IL, NH, OK, PA, VT) report all licensed child care providers participating in QRIS, and six lagging states (NJ, NY, CA, TX, ID, ND) report more than 80% of providers who do not participate in QRIS.

Source: The Build Initiative & Child Trends. (2021). A Catalog and Comparison of Quality Initiatives (Data System). Retrieved from http://qualitycompendium.org/ on August 17, 2022. Data are unavailable for 13 states: 4 states do not currently have a QRIS, five states are currently planning or piloting a QRIS, and 5 states have QRIS but do not report participation data.

For additional information regarding calculation details, data quality, and source data please refer to Methods and Sources.

For more information on outcomes by goal, including by race and ethnicity and state, see the 2022 Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap section on outcomes across the US.

WHAT ARE THE MOST EFFECTIVE STRATEGIES TO IMPACT NURTURING AND RESPONSIVE CHILD CARE IN SAFE SETTINGS?

Based on comprehensive reviews of the most rigorous evidence available, the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center identified 11 effective solutions that foster the nurturing environments infants and toddlers need. For each of the five policies, the evidence points to a specific policy lever that states can implement to impact outcomes. For the six strategies, the evidence clearly links the strategy to PN-3 outcomes, but the current evidence base does not provide clear guidance on how states should implement each strategy to positively impact outcomes. Two strategies have demonstrated effectiveness at promoting nurturing and responsive child care in safe settings.

For more information on the impact of state-level policies and strategies in the prenatal-to-3 period, search the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Clearinghouse for an ongoing inventory of rigorous evidence reviews. To learn more about the impact of effective policies and strategies on the eight prenatal-to-3 policy goals, see the Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap.

WHAT OTHER SOLUTIONS ARE STATES PURSUING THAT CAN HELP BUILD THE EVIDENCE BASE?

Beyond the strategies proven effective by the current research, states also are pursuing other approaches that hold promise for improving nurturing and responsive child care in safe settings; these approaches have not yet accumulated enough rigorous research to enable drawing conclusions on their effectiveness, or the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center has not yet conducted a comprehensive evidence review for the approach. Other solutions states are pursuing that can help build the evidence base on nurturing and responsive child care in safe settings include, but are not limited to:

- Quality Rating and Improvement Systems, which are methods of assessing, improving, and communicating the level of quality of care in early care and education (ECE) settings;

- Child care coaching, which are a means of professional development that connects caregivers in the ECE workforce with child care experts to help them improve their skills through an ongoing, collaborative process;

- Improving child care ratios, which includes setting child care ratios – the number of children per adult caregiver in the same room in an ECE setting – to promote quality and safety;

- Promoting child care workforce qualifications, which may include setting requirements for teachers’ levels of pre-service educational attainment and specialized training; and

- Supporting strategies to improve child care workforce compensation, which may include salary guidelines or financial relief strategies (e.g., tax credits, bonuses, stipends, and scholarships) to improve the wages and benefits provided to the ECE workforce.

SOURCES

- Center on the Developing Child. (n.d.). Serve and return. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return/

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2012). The science of neglect: The persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing brain: working paper 12. http://crisisresponse.promoteprevent.org/sites/default/files/projectlaunch/the_science_of_neglect.pdf

- National Research Council. (2012). The early childhood care and education workforce – Challenges and opportunities: A workshop report. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13238/the-early-childhood-care-and-education-workforce-challenges-andopportunities

- Shonkoff, J. (2014). A healthy start before and after birth: Applying the biology of adversity to build the capabilities of caregivers. In K. McCartney, H. Yoshikawa, & L. B. Forcier (Eds.), Improving the Odds for America’s Children (pp. 28-39).

- Otten, J. J., Bradford, V. A., Stover, B., Hill, H. D., Osborne, C., Getts, K., & Seixas, N. (2019). The culture of health in early care and education: Workers’ wages, health, and job characteristics. Health Affairs, 38(5), 709-720. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31059354/

- McLean, C., Austin, L. J. E., Whitebook, M., & Olson, K. L. (2021). Early Childhood Workforce Index – 2020. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2020/report-pdf/

- Child Care Aware of America. (2019). The US and the high price of child care: An examination of a broken system. https://www.childcareaware.org/our-issues/research/the-us-and-the-high-price-of-child-care-2019/

- Burchinal, M. (2010). Differentiating among measures of quality: Key characteristics and their coverage in existing measures, OPRE Research-to-Policy, Research-to-Practice Brief OPRE 2011-10b. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/differentiating-among-measures-quality-key-characteristics-and-their-coverage-existing

- Gordan, R. A., Fujimoto, K., Kaestener, R., Korenman, S., & Abner, K. (2013). An assessment of the validity of the ECERS-R with implications for measures of child care quality and relations to child development. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 146-160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027899.

- Mulligan, G., & Flanagan, K. (2006). Findings from the 2-year-old follow-up of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, birth cohort (ECLS-B). Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES 2006-043). https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006043.pdf

- Fuller B., Kagan, S. L., Caspary, G. L., & Gauthier, C. A. (2002). Welfare reform and child care options for low-income families. Future Child, 12(1):96-119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1602769.pdf

- Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Do you believe in magic? What we can expect from early childhood intervention programs. Social Policy Report, 17(1), 3-15. doi:10.1002/j.2379-3988.2003.tb00020.x

- Wright, T. S. (2011). Countering the politics of class, race, gender, and geography in early childhood education. Education Policy, 25(1), 240-261. doi:10.1177/0895904810387414