Two-generation programs for parental employment are theoretically aligned with these policy goals:

SUMMARY

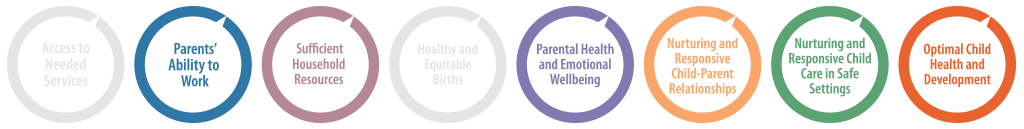

Two-generation programs for parental employment are theoretically aligned with these policy goals:

Two-generation programs for parental employment can increase access to needed services and parents’ ability to work, but evidence is mixed. Current studies do not, however, consistently link these programs to higher wages or better child outcomes. Additionally, two-generation parental employment programs have not yet been studied as a statewide policy, therefore the current evidence base does not provide clear guidance for state action. Further study, particularly on families with infants and toddlers under age 3, is needed to draw a strong conclusion, due in part to the lack of uniformity across programs and inconsistent program participation.

Two-generation programs for parent employment are services and programs that serve both children and their parents simultaneously, aiming to empower parents to secure and retain gainful employment while providing children with support needed for successful early development. Such programs maximize the benefit to families by ensuring parents are able to access employment training and other support services without sacrificing quality care for their children. Helping parents find and retain employment can provide them with the resources to foster a safe and healthy environment for their children to develop. Funding for these programs has come from all levels of government and private foundations, but initiatives to deliver two-generation programs have largely taken hold at the state and local levels, rather than federally.

Download the Complete Evidence Review

Two-Generation Programs for Parental Employment Evidence Review (PDF)

Recommended Citation:

Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. (2020). Prenatal-to-3 policy clearinghouse evidence review: Two-generation programs for parental employment (ER 0920.019A). Peabody College of Education and Human Development, Vanderbilt University. https://pn3policy.org/policy-clearinghouse/two-generation-programs-for-parental-employment