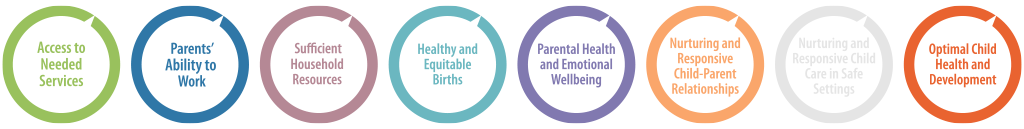

Paid family leave positively impacts these policy goals:

SUMMARY

A paid family leave program of a minimum of 6 weeks is an effective state policy to impact:

A state policy providing at least 6 weeks of paid family leave to parents with a new biological, adopted, or foster child increases the likelihood and length of leave-taking for mothers, reduces racial disparities in leave-taking, and has beneficial effects on maternal labor force attachment, postneonatal infant mortality, parent and child health, and nurturing and responsive parenting.

Paid family leave policies require employers to allow eligible parents to take time off from work to bond with a new child while receiving a portion of their salary. By providing parents with the time and financial security to stay home with a new child, paid family leave may improve both economic security and the health and wellbeing of children and parents. Currently, 14 states, including the District of Columbia, have enacted statewide paid family leave policies of any length. Only nine states have begun implementing a paid family leave policy of at least 6 weeks as of October 1, 2023.

States vary in the number of weeks offered, the portion of wages paid, eligibility requirements, job protection provisions, and funding mechanisms. States also vary in whether they provide leave to employees in the private sector, the public sector, or both. Studies that examine the causal impact of paid family leave policies find that providing at least 6 weeks of paid leave to parents with a new child increases the length and likelihood of leave-taking, increases mothers’ labor force participation rates, improves mothers’ mental health, and fosters better child-parent relationships and child health.

Download the Complete Evidence Review

Paid Family Leave Evidence Review (PDF)

Download the 2-Page Summary

Paid Family Leave: An Effective Policy to Improve Child and Parent Outcomes (PDF)

Recommended Citation:

Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. (2023). Prenatal-to-3 policy clearinghouse evidence review: Paid family leave (ER 03D.0923). Peabody College of Education and Human Development, Vanderbilt University. https://pn3policy.org/policy-clearinghouse/paid-family-leave

Updated October 2023